这篇由Alexander J. Lee撰写的文章是我们第七届年度学生编辑大赛高中组的前9名获奖者之一,我们收到了6,076份参赛作品。

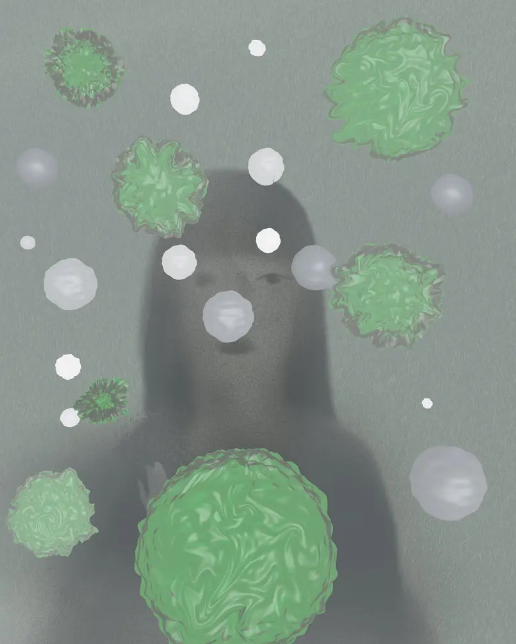

插图:Jon Han

A few weeks ago, my friend arrived at our lunch table in tears. She’d come from physical education class, where a group of white classmates called her “coronavirus” for her Chinese heritage. It hurt my friend, who hadn’t heard from her relatives in Wuhan. That incident wasn’t isolated — other Asian-American students were targeted for their ethnicity at our middle and high schools. Throughout February and March, similar scenes played out at schools across the country, with Asian-American students insulted and harassed by other students.

One might think that this behavior reflects the numerous anxieties Americans face due to the coronavirus pandemic, including economic insecurity. But my community is affluent and well-educated, my neighborhood dotted with lawn signs saying “Hate Has No Home Here.”

Instead, the coronavirus-fueled bias against Asian-Americans is symptomatic of a wider phenomenon: American society has always regarded Asian-Americans as “non-American.”

Many Americans, of all stripes, are unfamiliar with the breadth of cultures and backgrounds that “Asian-American-ness” comprises. Without that awareness, it’s easy to paint a generic picture of Asian-Americans with broad, stereotypical brush strokes: industrious, high-achieving, passive and foreign. A local university thinks we lack “personality.” This unfamiliarity leads to a subconscious categorization of Asian-Americans as being “other,” a one-size-fits-all group too different to be fully “American.”

Nearly every Asian kid (myself included) experiences this categorization through the question, “Where are you really from?” It doesn’t matter that I was born in Boston, or that my dad cried tears of joy when his hometown team won the World Series “after 108 years of futility.” It’s usually an innocuous question phrased poorly, and I’ll happily talk about my background, but it assumes that Asians can’t quite be considered “American.” That assumption quietly breeds suspicion, and suspicion breeds fear.

We’ve seen this fear of the unfamiliar, combined with external “proof” that Asians “threaten the American way of life,” give rise to active discrimination, from the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, to Japanese internment during World War II, to the verbal and physical attacks of today. This is only possible because Asian-Americans were always viewed with suspicion. For sure, the Communist Party of China has been untrustworthy, but it doesn’t justify linking my Chinese-American friends to the coronavirus. President Trump’s “Chinese Virus” label holds power against Asian-Americans because they’re seen as outsiders — it taps into the fear and anxiety that Americans feel, and the need to displace that fear.

Yet, the coronavirus, and the heightened bias associated with it, gives Asian-Americans a unique opportunity to hold a national dialogue about being “forever foreigners” — to go beyond cultural stereotypes and share our individual experiences. By approaching one another as human beings, not faceless “others,” we might someday view each other as Americans first.

Works Cited

Bittle, Andrea. “I Am Asian American.” Teaching Tolerance, 2013.

Hong, Cathy Park. “The Slur I Never Expected to Hear in 2020.” The New York Times Magazine, 12 April 2020.

Oung, Katherine. “Coronavirus Racism Infected My High School.” The New York Times, 14 March 2020.

Pan, Deanna. “Fears of Coronavirus Fuel Anti-Chinese Racism.” The Boston Globe, 30 Jan. 2020.

Yang, Andrew. “Andrew Yang: We Asian Americans Are Not the Virus, but We Can Be Part of the Cure.” Washington Post, 1 April 2020.