By Salma Reda, age 16, Jumeirah College, Dubai

Credit...Alessandra Montalto/The New York Times

Whether she does it via a thorough polysyndeton (“tall and thin and blond and pretty and young”) or a gnomic vulgarity (“hot shit”), the unnamed protagonist of Ottessa Moshfegh’s “My Year of Rest and Relaxation” will make sure you know she’s beautiful. Speaking from a strange, morbid enclave between consciousness and unconsciousness, the central character provides a whole host of these self-diagnosing insights. Speaking of self-diagnosis, she’s just about to take three lithium, two Ativan and five Ambien. Check it out.

Set in pre-9/11 New York City, Moshfegh’s 2018 novel has all the decadent ennui of brilliant fin-de-siècle literature. The beautiful, recently orphaned scion of an affluent WASP family, our main character initially “just wanted some downers to drown out my thoughts and judgments.” In a furiously fatigued buildup, she decides she wants to spend as few hours of the day awake as possible. “A year of rest and relaxation,” she dubs her quest to lull herself into a narcotic-induced state of unconsciousness. She’ll finally be rid of all the bulky appendages that come with being awake: her needy college friend Reva, her older kind-of-boyfriend Trevor, her quack doctor Tuttle (“whore to feed me lullabies”) and her creepy art-gallerist friend Ping Xi. Every aspect of the protagonist’s privileged Y2K milieu is realized with withering causticism. This is where Moshfegh’s writing thrills — in her scathing social taxonomy. A particularly damning passage in which she describes her finance-bro boyfriend Trevor: “I’d choose him a million times over the hipster nerds … reading David Foster Wallace, jotting down their brilliant thoughts into a black Moleskine pocket notebook … passing off their insecurity as ‘sensitivity’.” Moshfegh breathes new life into that eternal dichotomy — jock versus nerd, cultured versus uncultured — all with the somehow-timeless syntax of gauche 2000s pop culture.

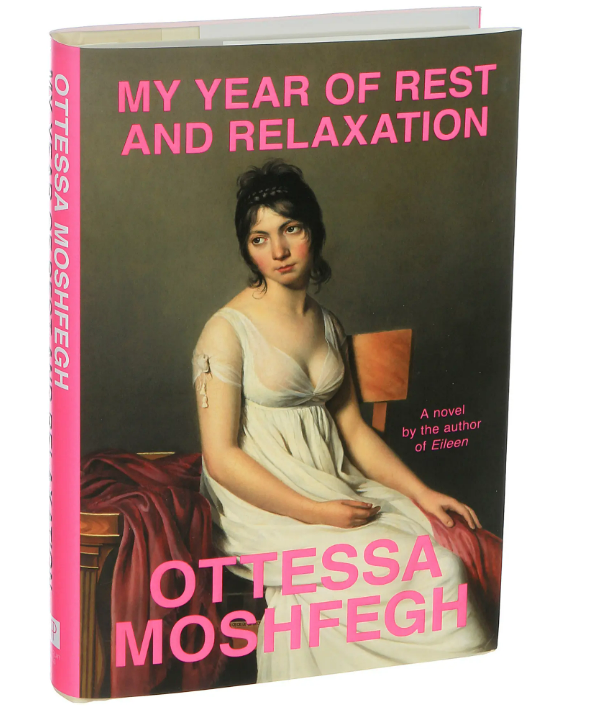

Toward the end of the novel, the protagonist’s bumbling doctor contends, with uncharacteristic penetration, “look deeper and deeper and eventually you’ll find nothing. We’re mostly empty space. We’re mostly nothing.” I’m not wholly inclined to believe Moshfegh’s performed misanthropy, though. Undergirding “My Year of Rest and Relaxation” is a wonderful, anachronistic reverence of art. Whether it’s in the 19th century portraiture that graces the now-iconic cover, or the main character’s art history education (“cultured,” she calls herself, with a halfhearted narcissism), it’s clear that Moshfegh is deeply protective of art. “I’ve dedicated a lot of my life as a writer to understanding … the music of the spheres,” she confesses in an interview, with an almost hippyish worldliness.

For a pandemic-ridden populace, the protagonist’s soporific chrysalis takes on a newly appealing allure. For that enduring subsection of the population — the eternal group of malcontented teenage girls enamored with a beautiful-yet-tortured ideal — the novel should delight.