By Lyat Melese, age 16, Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology, Alexandria, Va.

Credit...Illustration by Melinda Josie

The shrill sound of a whistle slices through the gym, slowly halting the bouncing basketballs, squeaking tennis shoes and background chatter. My P.E. teacher stands in the middle of the room, looking around in distaste at the disarray of basketballs, hula hoops, and volleyball nets. He asks for volunteers to help clear the gym.

Saanvi raises a lone hand into the air. Everybody else refuses to meet the teacher’s eyes, focusing on the floor, their hands or the ceiling.

I sigh as it strikes again.

Yilugnta

It is hard to define the Amharic word in English. It describes the feeling comprising a mishmash of extreme empathy and the inability to say “no.” It is a trait I see in my mother and, much to my annoyance, myself. While yilugnta makes me a kind and respectful daughter at home, it makes me a pushover susceptible to guilt-tripping at school.

I raise my hand, “I can do it.”

Saanvi and I collect all the balls and ropes, rolling the carts into the storage room.

We are alone when she suddenly stops and looks at me.

“Did you get accepted?” she asks, referring to the highly selective admission to the local STEM high school.

“Yeah,” I reply. “You?”

She looks away. Her hands fist at her sides as a frown is etched on her face.

I look down. “I’m sorry. I know how badly you wanted to go.”

“You don’t understand,” she spits out. “You obviously got in because you are Black.”

I don’t respond, focusing instead on the colorful hula hoops I am stacking in a pile: green, yellow, blue.

When we first moved to America, my parents went to great lengths to avoid the term “Black.” They instilled in me that I was not just Black, I was Ethiopian. I used to think it was because they didn’t want me to forget my culture. Now I think they were protecting me because the term “Black” shoulders the weight of history.

My Nigerian neighbor always grits his teeth and talks to himself when he watches Nigerian news. He blames Britain for forcing the tribes together. He says Nigeria should not have existed. Now, his wife hides the remote because his blood pressure grows too high.

My mom’s friend’s African-American partner goes to town halls and protests every week. He still waits for the day he will get the reparations his ancestors were owed.

My mom tells me that we are not like them. Our ancestors were not colonized or enslaved. Don’t carry the burden that is not yours.

In my head, I want to scream that I did not choose to carry anything. It was shoveled on top of my head. Much like my yilugnta, it is a trait I have to own, no matter how I wish otherwise.

The age of shackles and scramble for land has long passed, but the aftermath reverberates in our ears, whispering words like “victim,” “predator” and “diversity hire.”

Black is black is black.

I turn back to look at Saanvi.

“The admissions are race-blind,” I state.

“Everybody knows that’s not true,” she scoffs. “So few Black people apply, you are guaranteed a spot.”

She pushes past my shoulders and marches out of the room.

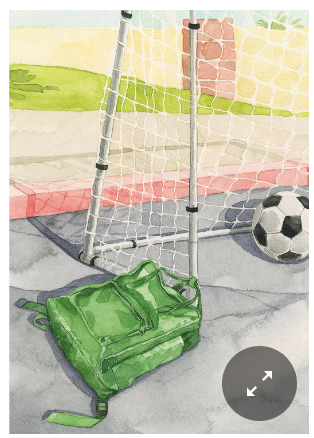

Her bag lies forgotten on the floor, a key chain with a colorful peace sign dangling from the front.

I stare at it, contemplating leaving it there.

Yilugnta

I pick up the straps and haul it over my shoulder, once more carrying the weight I do not own.

_________