By Aaron Wang, 16, Regis High School, New York, N.Y.

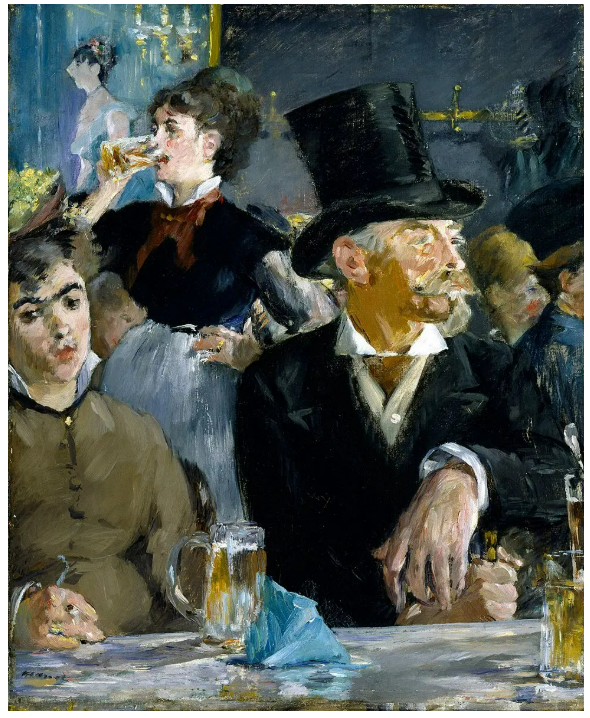

Manet’s “The Café-Concert,” circa 1879. Aaron Wang, 16, writes that this painting “echoes a modern feeling: being physically close to someone but feeling disconnected in spirit.”

Have you ever felt alone in a crowd? Well, that sensation is nothing new! It was alive and well in Paris in the 19th century, a city on the cusp of modernization. The four artworks below were painted in the span of one decade and offer scintillating snapshots of how artists captured the paradoxical cocktail of excitement and alienation that Parisian citizens felt as they headed full force into modernization. By illustrating how modernization pushes people apart emotionally, these works resonate with anyone navigating today’s fast waves of technological modernization. Stepping back into 19th-century Paris, you’ll sense the pulse of a changing city and find echoes of our own landscape. I highly recommend you check them out, I have, and they’ve made a difference in how I gaze at art, modernity, and the human condition amid change.

First is Edouard Manet’s “The Café-Concert” capturing two figures seated side by side in a Parisian cafe. At first glance, they appear to be sharing a moment, but a closer look reveals their detached gazes: neither looks at the other, and both seem lost in private thoughts. In a city experiencing explosive growth and modernization, Manet highlights how people could sit elbow-to-elbow yet remain miles apart emotionally. The blurred background and loose brushwork intensify the sense that each figure is trapped in their own world. I find this painting striking as it echoes a modern feeling: being physically close to someone but feeling disconnected in spirit.

Edgar Degas’s “L’Absinthe” shares similar themes of isolation, but the mood is heavier. The subdued browns and grays set a somber tone as a man and woman sit together without actually connecting. Their vacant stares seem to push them into their own worlds. By capturing this tense quiet, Degas hints at the loneliness that can lurk beneath the surface in any large city. His muted palette echoes a heavier sense of direct melancholy, heightening the painting’s depiction of silent alienation. I find “L’Absinthe” a powerful reminder that crowds in a buzzing metropolis don’t necessarily cure loneliness.

Returning to Manet, we find another variety of detachment in “A Bar at the Folies-Bergère.” Here, a barmaid stares out at us with a distant, haunted expression. Behind her, a mirror reflects the vibrant nightlife and a male customer leaning toward her. The viewer is effectively placed in the man’s position, compelled to acknowledge our role in staring. This forced perspective challenges the viewer to consider how consumer culture can turn people into commodities and thus create alienation.

By contrast, Mary Cassatt’s “In the Loge” places the audience in the position of the subject of a male gaze, a different but equally isolating dynamic: both the female figure watching the opera and the viewer are scrutinized by a man in the background. Here, audiences become Manet’s barmaid. We experience alienation from the vantage point of being observed. In the process, Cassatt highlights how, even in the swirl of social events, the pervasive awareness of another’s gaze can intensify our own sense of isolation.

Each of these four paintings reveals a city alive with energy yet tinged with loneliness. Through subtle gestures and unwavering stares, the figures embody a universal human tension: navigating the chasm between public spaces and private feelings. They also stir insights into how modernization not only reshaped 19th-century Paris but continues to define our sense of belonging and isolation today. The next time you stroll through a crowded street or a cramped cafe, remember these images. They show that while modern life can bring us closer physically, it doesn’t always guarantee a true connection.