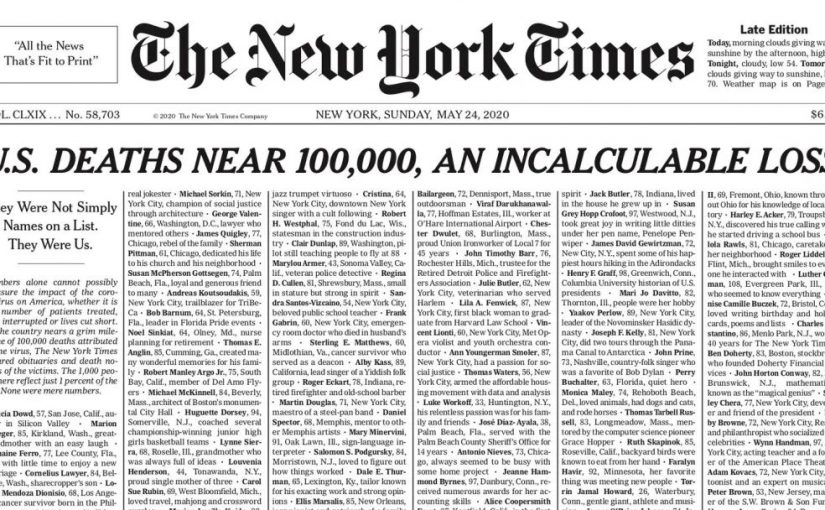

作为全球知名的媒体,《纽约时报》举办了各种中学生系列竞赛来提升学生的写作能力。这些竞赛可谓含金量高,而且完全免费!此外,成功参赛并获得奖项还可以获得奖学金,对于冲刺名校的人文社科类学生可以说是一大福音。

纽约时报写作比赛每年都吸引了来自世界各地的数万名学生参加。比赛的参赛过程并不容易,需要参赛者在规定的时间内写出符合主题要求的文章。但这个过程对于参赛者的灵魂与思想却是一次非常好的淬炼与打磨。

对于那些有志于进入名校的学生来说,参加纽约时报写作比赛是一次非常难得的机会。参赛者可以展示自己的才华,进一步提高自己的写作能力。同时,获得奖项还可以在将来的学习生涯中提供资助。

2023年目前仍在可以报名参加的竞赛

社论比赛

竞赛时间:2023年3月15日-4月12日

作品要求:

选择一个你关心的话题,并提出一个能说服读者也关心这个话题的论点;

社论文章字数不超过450字,所以要确保论点足够集中,并提出有力的论据;

至少使用一份发表在《纽约时报》上的文章和一份来自《纽约时报》以外的文章作为论据;

社论比赛可以个人参赛也可以小组参赛,但每个学生只能提交一篇社论文章。

播客挑战赛

竞赛时间:2023年4月12日-5月10日

作品要求:

创建一个播客,需要以清晰的开头、中间和结尾构成一个完整的作品。

不限播客格式或风格,时长不超过5分钟。

必须为未发表的原创作品

学生可组队共同创建播客,但每个学生只能提交一个作品

使用不受版权保护的音乐,使用的音乐请列明出处

暑期阅读挑战赛

竞赛时间:2023年6月9日-8月18日

作品要求

作文字数不超过1500个字母,相当于250-300个左右英文单词。

每周都可以参赛,连续10周,每周都会有冠、亚、季军。相当于每周都有一次参赛获奖机会。

提交作文时需提交话题原文链接或完整标题。

如果你也对纽约时报写作竞赛感兴趣,想要在众多申请者中脱颖而出,快来扫码领取报名表~

扫码免费领取往届优秀获奖作品

咨询报名注意事项+预约试听体验课

预约最新真题讲座、课程详情可添加下方顾问老师咨询

纽约时报写作比赛不仅是一次写作比赛,更是一次提升自己的机会。如果你想挑战自己,展示自己的才华,不妨参加纽约时报写作比赛,相信你一定能够收获不少!