我们通过发表论文来表彰学生 STEM 写作比赛的前 11 名获奖者。这是艾琳·拉斯穆森(Erin Rasmussen)的作品。

The World’s Best Quarantiners

We think that quarantining for the past year has been hard, but cicadas have been doing it for the past 17 years, and they’ve chosen 2021, of all years, to come out.

Cicadas are a very loud species of insect that live over 99 percent of their lives beneath our feet. They live about one to two feet underground as wingless nymphs until they feel ready to come out. Some cicadas come out annually, but others spend 13, or even 17 years underground. These “periodical cicadas” are planning on coming out in 2021.

Cicadas are know for making noises as loud as a lawn mower, or about 90 decibels. That’s loud enough for the Occupational Safety and Health Administration to require hearing protection. So, be sure to bring your ear plugs if you want to see these little bugs.

If you were alive in 2004, you might remember the constant buzzing and the exoskeletons that the cicadas left behind. However, if you missed it then, your best chance of seeing a cicada will be in the South, but they will be as far north as New York.

Although they might be annoying, cicadas are perfectly harmless. If you get really hungry at some point this summer, don’t hesitate to take a big, juicy bite of a cicada because they are edible. In fact, they are great sources of protein and very low in cholesterol. Though you might think this sounds pretty gross, people in ancient Greece and Rome considered cicadas a delicacy. Cicadas have been known to be cooked into tacos, pizzas, pies and even dumplings.

Just like Rapunzel, cicadas spend the first 17 years of their life away from the world for their safety. However, cicadas don’t need Mother Gothel to tell them to stay hidden from the outside world. They do it voluntarily. Cicadas will only come out when the conditions are just right. The soil temperature has to be above 64 degrees Fahrenheit (about 18 degrees Celsius), and it cannot be raining. Large groups of cicadas will emerge together when the time is right. However, according to Howard Russel, an entomologist (an insect scientist), “No one knows what mechanism they use to trigger their mass emergence.”

For humans, your 17th birthday is just that awkward one between your Sweet 16 and your big 18 I’m-finally-an-adult birthday. For a periodical cicada, 17 is the most important one. So, get your party hats on, because it’s about to be the biggest birthday of the bug world in 17 years.

Works Cited

Bachtel, Carl. “Billions of 17-Year Cicadas Expected to Emerge in 2021.” abc10.com, 26 Feb. 2021.

Matheny, Keith, Georgea Kovanis. “Brood X Periodical Cicadas, Underground for 17 Years, Ready to Re-emerge and Make Some Noise.” USA Today, 26 Jan. 2021.

Perkins, Sid. “Here Comes Swarmageddon!” Science News for Students, 3 Dec. 2019.

“Watch a Cicada Transform.” Cicada Mania, 30 June 2019.

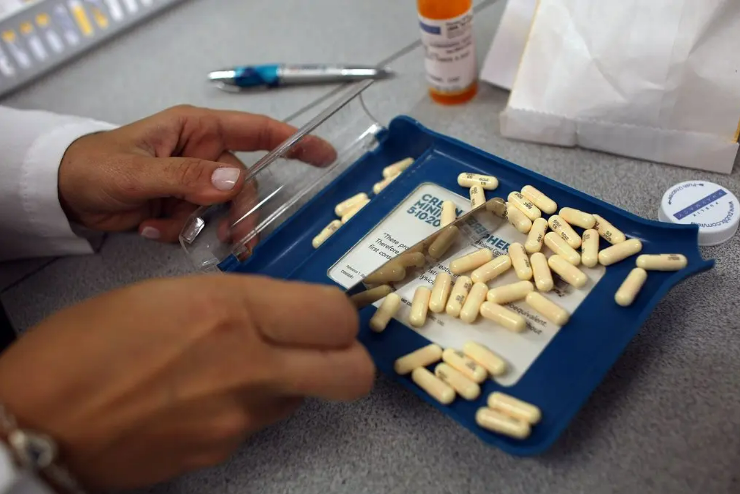

从左上角顺时针方向:“活着:不朽的水母如何欺骗死亡”;“颜色与大脑:我们都只是调色板的木偶吗?“从敌人到朋友:我的杀手止痛药”;“美味的罗非鱼:你的下一个绷带?和“干鼻Covid-19疫苗:无痛和无针的替代品”

从左上角顺时针方向:“活着:不朽的水母如何欺骗死亡”;“颜色与大脑:我们都只是调色板的木偶吗?“从敌人到朋友:我的杀手止痛药”;“美味的罗非鱼:你的下一个绷带?和“干鼻Covid-19疫苗:无痛和无针的替代品”