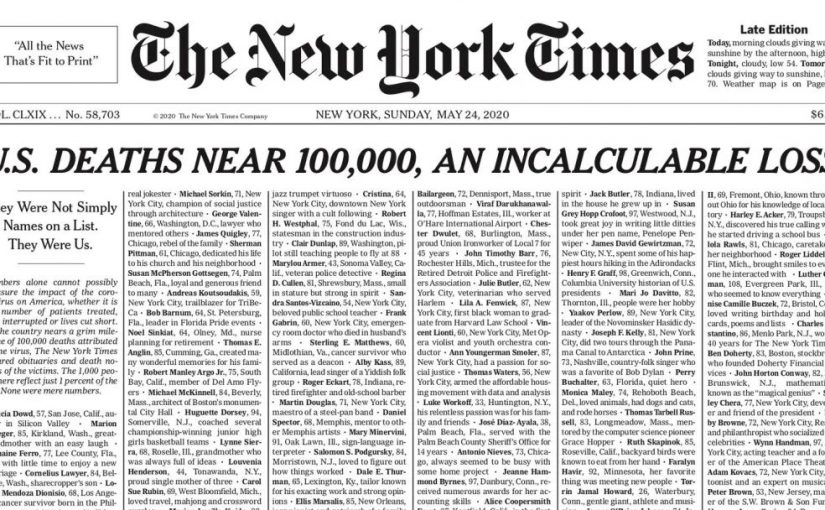

如果你喜欢写作,并渴望展示自己的才华,那么不妨参加纽约时报旗下的写作竞赛。不论你是理科生还是文科生,都可以在这里找到适合自己的比赛。纽约时报写作竞赛已经发布了2023年上半年的安排,请抓住机会参加这些比赛,让你的写作才华得到更多人的认可。参赛是一种挑战,但它也是一种成长和学习的机会。

2023上半年纽约时报写作竞赛安排已经出炉,看好时间别错过:

| 时间 | 项目 |

| 2022/09/14 -- 2022/10/12 | 100-Word Narrative Writing Contest |

| 2022/10/21 -- 2022/11/16 | Coming of Age in 2022: An Image Contest for Teenagers |

| 2022/11/16 -- 2022/12/14 | Review Contest |

| 2022/12/14 -- 2023/01/18 | One-Pager Challenge |

| 2023/01/18 -- 2023/02/15 | STEM Writing Contest |

| 2023/02/15 -- 2023/03/15 | Vocabulary Video Contest |

| 2023/03/15 -- 2023/04/19 | Editorial Contest |

| 2023/04/19 -- 2023/05/17 | Podcast Contest |

| 2023/06/09 -- 2023/08/18 | Summer Reading Contest |

如果你擅长理工科,那么STEM写作竞赛可能是个不错的选择。这个比赛将提供一个平台,让你展示你的科学、技术、工程或数学方面的知识,并以有趣的方式来表达它们。如果你赢得了这个比赛,将会获得奖金和荣誉证书。

除此之外,如果你喜欢关注时事和社会问题,那么社论比赛可能会吸引你。你将有机会撰写一篇主题广泛、有洞见的社论,以该问题的独特角度来展示你的思考和分析能力。这个比赛不仅可以帮助你提高解决问题的能力,还有可能赢得奖金和社会认可。

如果你有独特的成长经历,那么叙事写作竞赛也值得一试。你可以写出生活中真实发生的故事,让读者领略到你的感受、思考和成长。不仅如此,你还可以通过写作来强化自己的表达和写作能力,让自己的经历在人们心中留下深刻印象。

扫码免费领取往届优秀获奖作品

咨询参赛注意事项+预约试听体验课

预约最新真题讲座、课程详情可添加下方顾问老师咨询